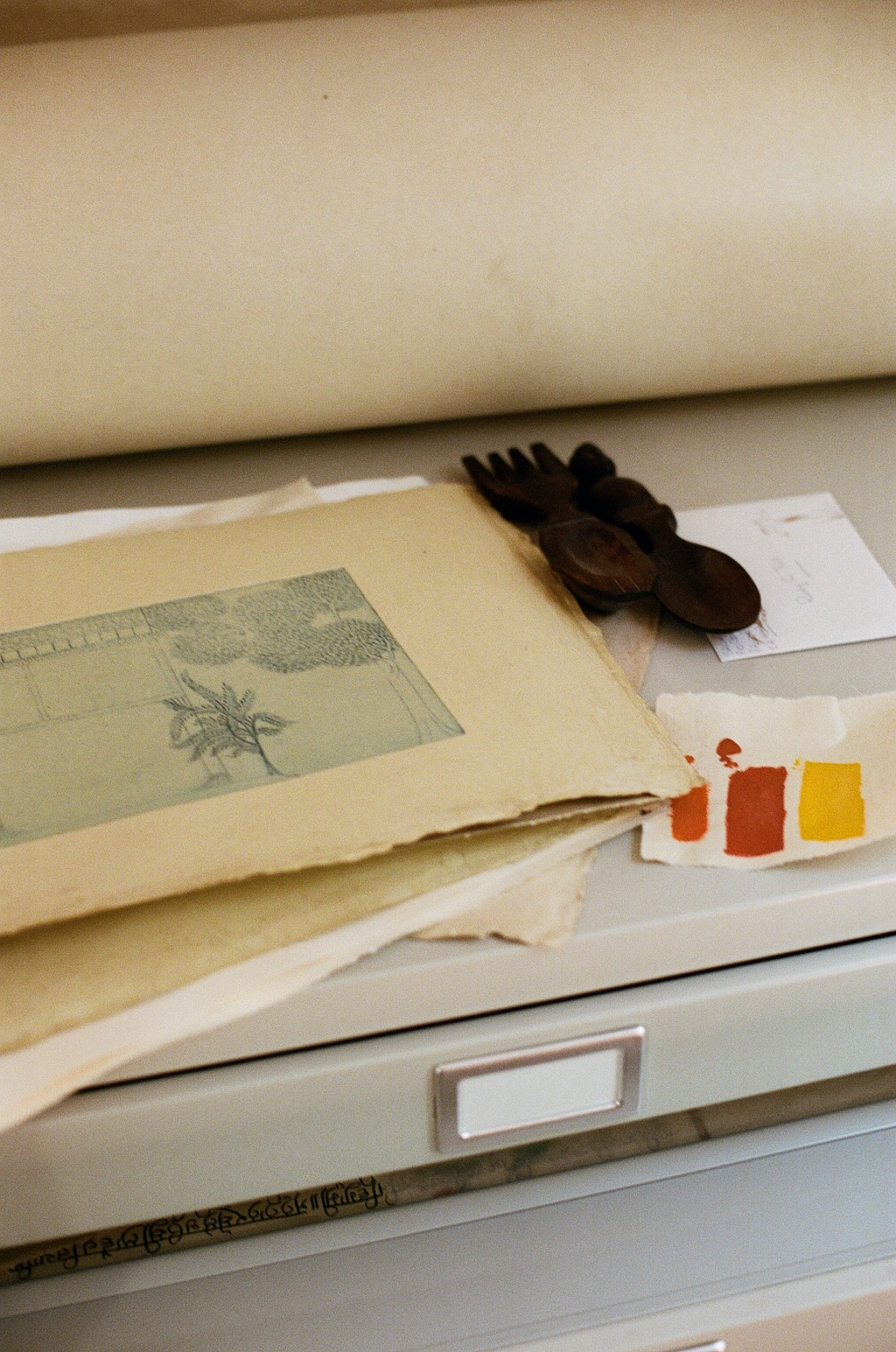

From her home studio in Oakland, Tut creates transcendent works using a centuries-old methodology of fine painting on paper. Engaging the histories embedded in her lived experiences and ancestral inheritances, she explores the intricacies of identity and belonging that connect the past, present, and future.

In Out of Place, Tut’s upcoming exhibition at the ICA SF, she continues to experiment within this traditional painting practice, embracing new mediums, narratives, and scales. The artist has collaborated closely on the exhibition with Gass, who encouraged Tut to seek the farthest reaches of her artistic ideation within the safe space of the museum, a newly founded gathering place centered on the Bay Area’s vibrant ecosystem of creative expression.

Chroma: For some people, home means comfort and ease, a place or space where we can fully be ourselves—or a person or people who validate and support us. Others experience home on more nuanced or even fraught terms as an environment or incarnation of judgment, suppression, or shame.

For you, Rupy, as an artist who interrogates narratives of identity, belonging, and displacement, as well as a descendant of refugees and a first-generation immigrant, how do you personally engage with the idea of home?

Rupy C. Tut: I feel like I’m going to spend the rest of my life figuring that out. And I have spent most of my life as an artist figuring that out: what is home for me? Because of the history that I sit with. I think of home as another family member, someone who is sometimes present and sometimes in the past or is lost or unreachable, or a person you could potentially not have connection to in the future.

Theoretically or ideologically, that’s how I think of home. But practically speaking, my home is where my studio is, and my practice overlaps my personal and professional life very, very closely. Home then, for me, is a place that allows me to be every label I associate with myself as a person, and where I can choose between all the different people that I want to be—anyone that I want to be in that moment.

In my paintings, it’s all about finding home through the lens of landscape, finding the ground you stand on—and does that ground feel shaky? Does that ground feel like it’s my own? And if it doesn’t, then these paintings are an effort to make it my own. My figures are, in some way, at rest, being themselves—or what they would be like in a place where they feel comfortable.

Chroma: You’re trained in a specific style connected to a place, a culture, and a history, but your approach is very contemporary. How do you navigate the complexities of both embracing and challenging tradition?

RT: Even as a little girl, I was always encouraged to question tradition, but also to embrace certain traditions that marked a way of belonging. Whether it was something subtle, like the way all the women in my family wear the dupatta. There is this sense that this is how I belong to these amazing women, if I wear it this way. But, at the same time, maybe they felt like they didn’t have a choice and were kind of conforming to patriarchal tradition within their personal or professional lives. That’s what I challenge, definitely for myself and my generation.

Within my work, I’m taking this male-centric view of this traditional way of making and then I’m bringing that into this female-centric view and female-centric ways of making and addressing and looking at the world. But I’m not actually building on that tradition. Because you can’t build on a tradition that’s built on something you are challenging to your deepest core.

There is also, for me, a distinction between old tradition and new tradition, because tradition is something that is not only of the past. It’s just one way of doing something, and it could be an old way of doing it or the new way of doing it. Like anything in life, tradition can be a good thing if I have a choice and I’m allowed to embrace it or challenge it, then it’s just a normal thing. It’s not an idea that feels suffocating as a person and as an artist. The visual tradition of the style I’ve been taught is very specific, but in my work there’s always an evolution or innovation because I know it so intimately.

Chroma: Alison, at the ICA SF, with your community-first ethos and exhibitions like Out of Place, you’re creating a place for connecting people to the expansiveness and relevance of contemporary art. Museums are vibrant and necessary centers of culture housing the embodiment of creative expression. But they are also historically gatekeeping institutions often catering to audiences of privilege. How are you nurturing a more curative idea of the museum for both your artists and community?

Alison Gass: Museums traditionally have been places where people often felt they had to stand at a remove, and where the broadest possible spectrum of audiences, artists, and community members maybe haven’t always felt welcomed. The ICA SF was founded in a moment when a lot of inequities in the art world were being laid bare. We had this great privilege to start a museum and put our values front and center, and those values are about being welcoming, being a free institution to mitigate some barriers to access, being a space for artists to really experiment and take risks, and being an institution that is about expanding the canon of the present and the future of art history.

As we work with our artists, we are talking and thinking all the time about how to push the boundaries of their practices. All of our shows are these moments when artists have this freedom to dig in and expand what’s possible. It’s a space that allows artists to think about, “what’s next for me?” Or “what do I have the opportunity to do?” And with that comes a very intentional engagement program that brings together all different ways of inviting the community in.

Museums have this legacy of people not feeling like they belong, but ideally they are places where people feel a sense of belonging in the broadest possible sense. That’s what we’re beginning to build so that everyone who comes in the door, there’s a part of them that does belong and there’s a part of the ICA SF that belongs to them, and then there’s this sense of comfort, of feeling at home.

Chroma: How does the ICA SF create an environment where artists feel comfortable and supported to experiment?

AG: It’s really about building trust and following our artists’ lead. We engage artists who have a really powerful language that helps people see the world beyond the walls of the museum, and maybe see themselves reflected back. With these artists who inspire us to understand or confront the issues happening in the world around us, we’re cultivating new kinds of lineages that feel the most relevant—the stories that haven’t been told, the stories that feel authentic to our communities. That feels really, really important—that people come in and they see work that feels meaningful to them.

RT: One thing that I found particularly, specifically different about the ICA was this sense of walking in and just being able to breathe. And that’s walking in as a person who has felt at times that my work would never be seen in spaces that are mainstream. When I look at spaces where I’m going to show my work, I think about my mom or my dad or my grandmother. When they walk in, are they going to be able to breathe? Are they going to walk in and think, “this is meant for me”? Every work I make is for people who have never had an opportunity to walk into a museum. Because maybe they’ll find it. At the ICA SF, it’s those lineages that are being nourished in that space that I felt people could breathe there.

Chroma: How do domestic spatial experiences affect your creative process?

AG: I couldn’t have a creative process without my home life, honestly, because my career is quite public-facing, and not in a bad way, but to be very “on,” representing the institution and telling the story of the artists, there’s an element that is performative. And home then, for me and my family, is a kind of anchor that allows me to be out in the world, and then when I’m at home, there’s this release. I can shed a little bit of that performance.

At the same time, the art world, especially the Bay Area art world, functions almost like connective tissue. So my social life is really the art world as well. And the Bay Area art world is uniquely warm and collaborative. My friends are the people I work with and not just at the ICA SF, but gallerists and other museum curators and supporters of the arts. There is this deep sense of connection and sharing, but then home is a place of real privacy for me, and I value that in a very powerful way.

RT: There’s another really big philosophy that I adhere to as a person and as an artist, and it’s that space can disappear in a second. That’s a remnant of the trauma that my family has been through. Space is essential to create work, to show work, but at the same time it’s also an entity that is transient and not permanent. Knowing that grounds my work in a truth and in a philosophy, rather than in an institution, or even me.

I take that very seriously, the ephemeral nature of things. If something happened five years from now or ten years from now or even tomorrow, would it be this home that I missed or what’s created within it? And it’s definitely what’s created within it. I don’t know if that’s a mechanism that developed as a grandchild of refugees or as an immigrant who had to say goodbye to her childhood home or as a human responding to modern society.

And maybe the remedy to all that is spaces like the ICA SF that create a sense of breathability, where the space doesn’t feel bigger than the person. You could say it’s healthy, but it’s also what should be desired—and attainable, hopefully—in the art world, because the space is never larger than the visitor who walks in or the artist who creates the work or the people who work there.

Rupy C. Tut’s exhibition Out of Place is on view at the ICA SF, September 23, 2023–January 7, 2024. Help keep the ICA SF free for everyone. Become a member.